On Thursday, November 20th, chapter members had a tour of the exhibit, “And Let Victory Tell the Rest: 250 Years of Shipbuilding in Greater Philadelphia,” at the American Swedish Historical Museum. The exhibit is on display until January 4, 2026.

One of our members prepared this review of some elements of the exhibit.

Last Thursday I went on a great tour of the American Swedish Historical Museum, with fellow members of the Oliver Evans Society for Industrial Archeology, given by curator Brett Peters. We heard many “behind the scenes” stories about the galleries and objects on display. We also saw their current special exhibition, “And Let Victory Tell the Rest: 250 Years of Shipbuilding in Greater Philadelphia.” The choice of the Swedish Museum for this exhibit pays homage to two Swedish-Americans whose inventions changed Naval warfare, John Ericsson (July 31, 1803 – March 8, 1889) and John Dahlgren (November 13, 1809 – July 12, 1870). The exhibit is curated by the National Museum of the United States Navy as part of Homecoming 250, the celebration of the founding of the US Navy and the US Marine Corps in Philadelphia in 1775.

As one of the nation’s premier shipbuilding and repair regions in the world, Greater Philadelphia has built many ships for the United States Navy from shipyards lining both sides of the Delaware River. From the early days of the Continental Navy during the American Revolution to the nuclear-powered warships of the Cold War, the region’s yards and drydocks were critical components of the Navy’s operations in defending America and its allies abroad. This exhibit showcases some of these ships, the people that helped build them and their role in Defending America.

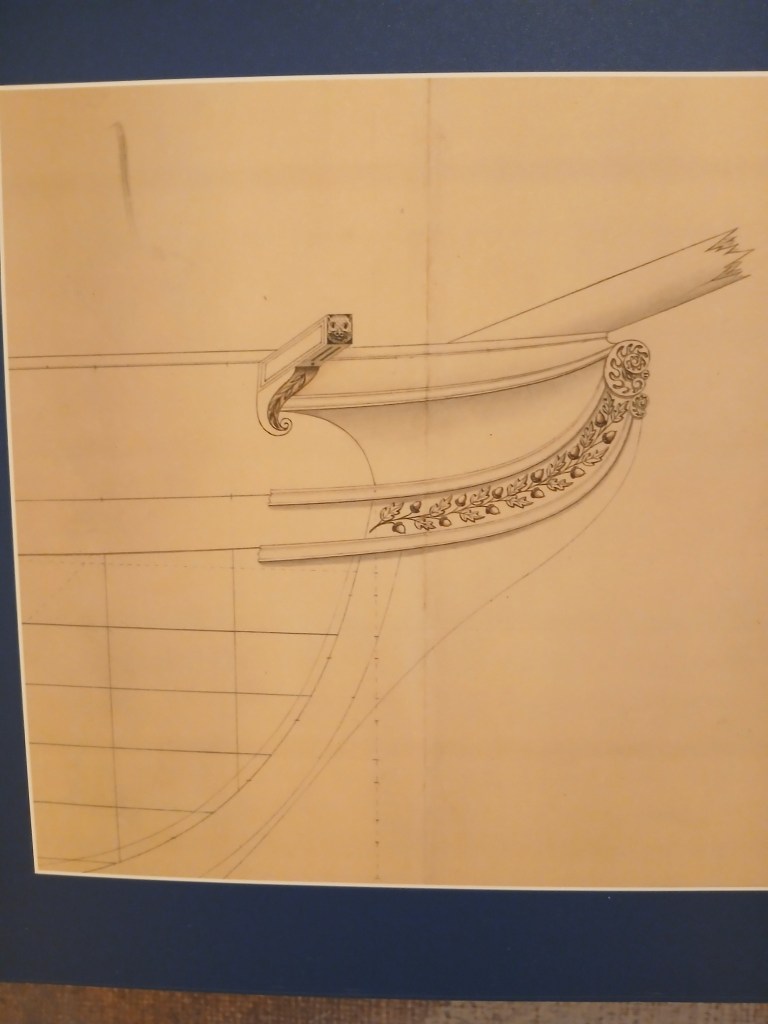

Bow of 1st Class Frigate, Joshua Humphreys, 1794, pencil on paper, courtesy of NARA

The genius behind America’s early warships was a Pennsylvania Quaker named Joshua Humphreys (June 17, 1751 – January 12, 1838). Already known for his work building ships for the Continental Navy, privateers and civilian merchants, citizens of the Early Republic took great pride in his vessels. On March 27, 1794, as part of the Naval Act of 1794, The US Congress authorized Humphreys to design and build the original six frigates of the United States Navy:

USS United States (1797)

USS Constellation (1797)

USS Constitution (1797) “Old Ironsides”

USS Chesapeake (1799)

USS Congress (1799)

USS President (1800)

Known as the “Father of the American Navy,” Humphreys taught the next generation of American naval architects. One of these apprentices later commented in awe of his teacher, “He designed them…and let victory tell the rest.”

Humphreys was born in Ardmore, PA, where he lived his entire life. His home still stands as a private residence. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joshua_Humphreys

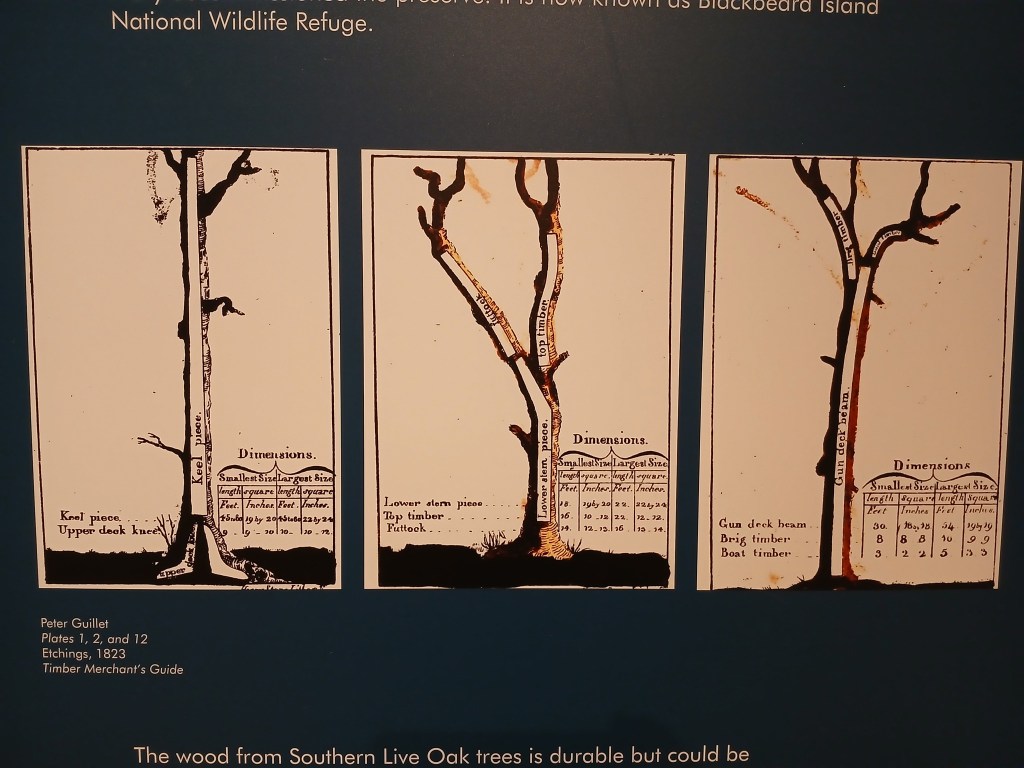

Timber Merchant’s Guide by Peter Guillet, Plates 1, 2 & 12, 1823

One of the unique characteristics of early American warships—including those built at The Philadelphia Shipyard—was the Navy’s use of wood from Southern Live Oak trees grown in the American South. Even though it was more expensive to process, senior naval officers advised that live oak would stand up better in combat and rough weather.

This position was proven during the fierce naval battle between the USS Constitution and the British frigate HMS Guerriere on August 19, 1812, off the coast of Nova Scotia. As the two ships exchanged broadsides at close range, the 18-pound iron cannonballs fired by the Guerriere were seen to bounce off the Constitution’s hull. An American sailor, observing this astonishing resilience, is said to have shouted, “Huzza! Her sides are made of iron!”. The nickname “Old Ironsides” quickly became popular and has endured ever since, symbolizing the ship’s strength and the American naval power it represented. The ship’s sides were made of a triple-layered hull of southern live oak and white oak, some of which was as much as 22 inches thick. This robust construction, combined with the fact that the Guerriere’s cannons were lighter than the Constitution’s, made the hull incredibly resistant to enemy fire.

To ensure a steady supply of the timber, the Navy acquired 6,000 acres of coastal land in Georgia for a live oak preserve in 1794. After supplying wood for 60 warships, the Navy decommissioned the preserve. Today it is the Blackbeard Island National Wildlife Refuge.

The wood from Southern Live Oak trees is durable but could be difficult to use efficiently due to its unique growth patterns (but these growth patterns are what give it its strength and resiliency). To help make the process of wood selection easier, naval architects produced guides like these for the Navy’s land agents to help them identify good candidates for the particular ship components that needed to be cut.

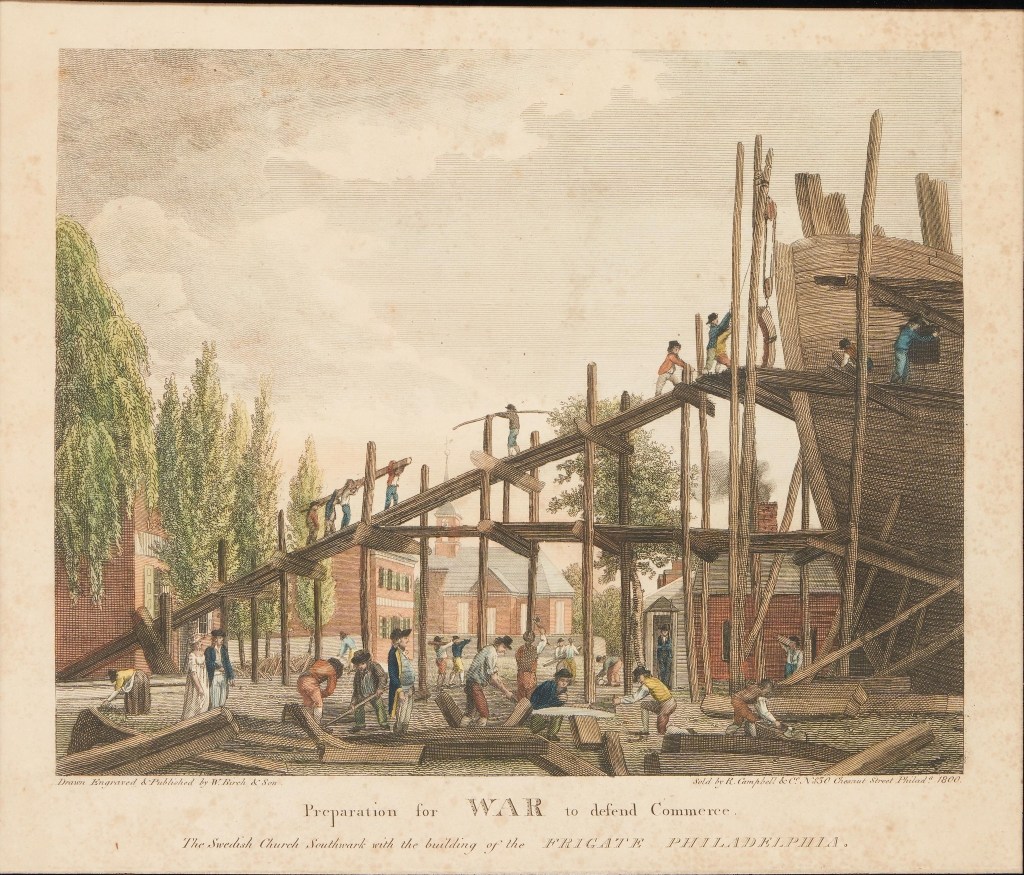

“Preparation for War to Defend Commerce. The Swedish Church Southwark with the Building of the Frigate Philadelphia,” by William Birch & Son, 1800, hand-colored engraving on paper.

Out of both a sense of patriotism and economic self-interest, America’s leading citizens pooled their money together to buy or “subscribe” ships for the new US Navy to supplement its primary warship program. In Philadelphia the committee commissioned naval architect Joshua Humphreys to design and build a frigate. Appropriately named “USS Philadelphia,” the 36-gun vessel set sail in 1800.

While touring the city pf Philadelphia in search of subjects to sketch, English artist William Russell Birch (1755–1834) came across Humphreys and his workers on Commerce Street building the Philadelphia. This was one of 27 engraved images by Birch and his son Thomas Birch (1779–1851) that appeared in their book Birch’s Views of Philadelphia (1800).

“Burning of the Frigate Philadelphia in the Harbor of Tripoli” by Edward Moran (1829–1901), 1897, oil on canvas, U.S. Naval Academy Museum Collection

The Philadelphia did not have much operational success despite its well-constructed design. Just three years after being launched, the she ran aground and surrendered to hostile forces in Tripoli during the War with the Barbary States. However, in one of the most celebrated moments in US naval history, on February 16, 1804, Lieutenant Stephen Decatur led a small raiding team into Tripoli harbor, recaptured the frigate and burned it to prevent it from being used by the opposition. Decatur and his team escaped without losing any of their own men, an action that was called “the most bold and daring act of the age” by British Admiral Lord Nelson.

John Ericsson, photograph, ca. 1861, Naval Heritage and Command collection.

As America became more industrialized, the US Navy slowly embraced new technologies. Steam-powered ships allowed captains to no longer be at the mercy of the wind and currents; new and bigger guns allowed the captain to hit an opposing ship at longer range and do more damage; and iron plates gave rise to the “ironclad” warship that could withstand more punishment that a wooden ship. With the national emergency caused by the American Civil War, the Navy accelerated its procurement of ironclads and other technologies.

John Ericsson’s first warship design was the steam-powered two-masted sloop USS Princeton. Working in partnership with shipbuilders at the Philadelphia Navy Yard, Ericsson oversaw the construction of this state-of-the-art vessel. Equipped with modern guns and a screw propeller for propulsion, the Princeton was the most advanced ship in the world in th 1840s.

Ericsson’s patented six-bladed propeller was one of the Princeton’s important features. Compact and more efficient than any other steam propulsion system of the day, his system allowed the Princeton to travel twice as fast as any ship under sail. The screw propeller, having been improved upon over time, has long been standard equipment on every ship in the world. His achievements revolutionized naval warfare and gained him international recognition.

FYI the Princeton suffered a tragic accident .For more on that, the Monitor, and Ericsson’s career watch this excellent video from ASHM’s You Tube Channel .

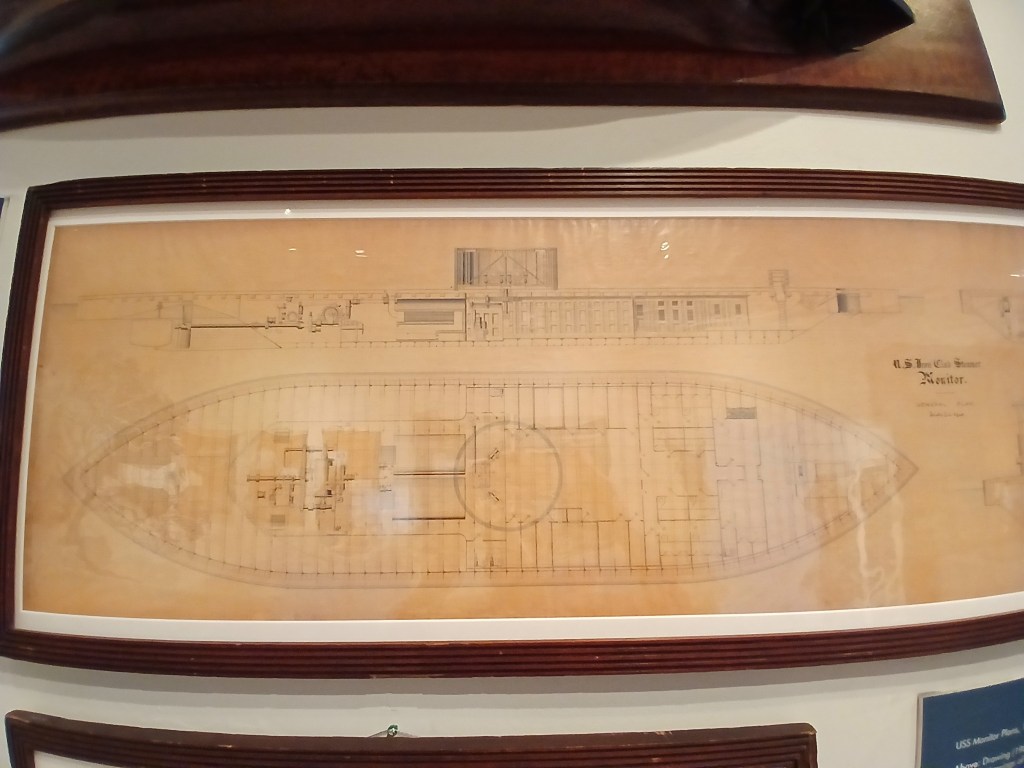

USS Monitor plans, 1862, American Swedish Historical Museum, gift of the John Ericsson Society.

Technical drawings of USS Monitor. Four different views on one sheet. One shows the whole ship as seen from above, another is a side view (placed above the first). To the right of these, and also above one another, are two transverse sections from different parts of the ship.

Ericson should be remembered for the design and creation of the screw propeller, but he is best known for the design of the USS Monitor.

At the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, both the Union and Confederacy began experimenting with ironclad warships. As the Confederacy began converting the captured USS Merrimac into the ironclad CSS Virginia, Ericsson signed a contract with the U.S. Navy to build an ironclad vessel for them.

Construction of the USS Monitor began in October 1861, and she was launched on January 30, 1862, in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, NY. Although its famous four-hour duel with the Virginia at the Battle of Hampton Roads in March 1862, was a tactical draw, the Monitor prevented the destruction of the Union fleet at Hampton Roads. After the battle, the Navy ordered another 56 of Ericsson’s “monitors,” as the design came to be known.

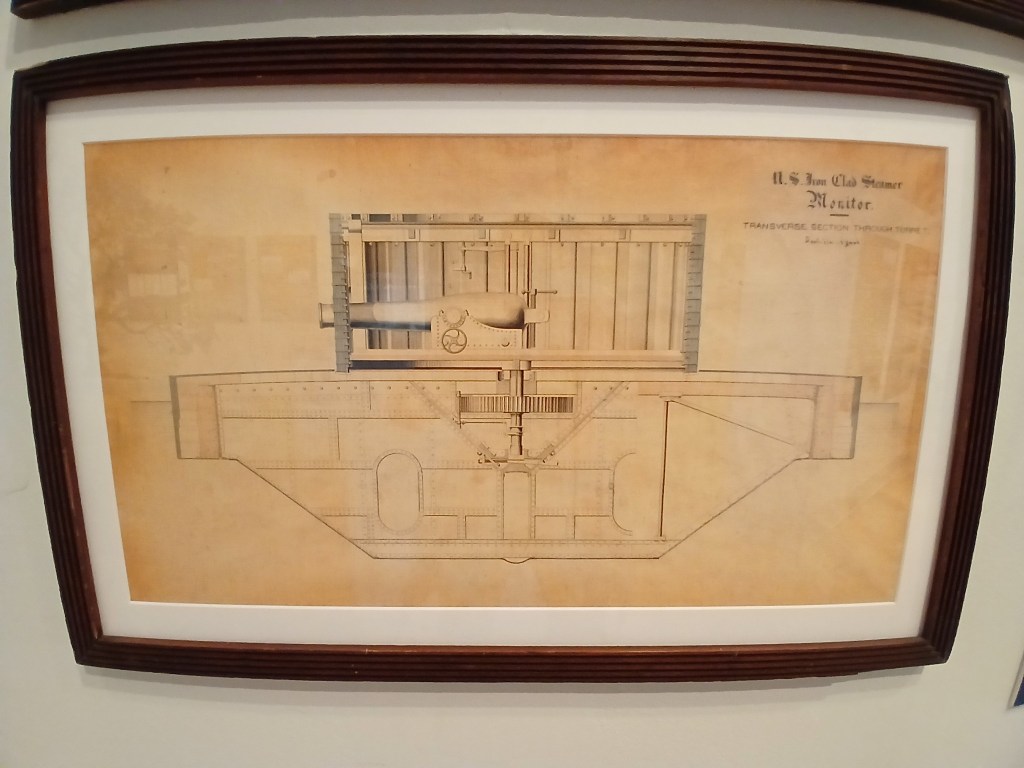

USS Monitor plans, 1862, American Swedish Historical Museum, gift of the John Ericsson Society. Technical drawing of the Monitor showing the transverse section through turret with a gun pointing to the viewer’s left.

Needing new ships to fight the Confederate States of America, the US Navy in 1861 solicited ideas for armored warships. Ericsson pitched his idea of a turreted warship. The turret in Ericsson’s prototype looked like a hat box (or “cheese box, as some would call it.) The ship was radical in design, and not just because it was made of iron. Ericsson gave the ship a low profile, making it harder to hit.

Ironically, the most recognizable feature, the “cheese box” turret, was not one of Ericsson’s inventions. A British architect named Cowper Phipps Coles patented the turret design in 1859 and Ericsson had to pay royalties for every monitor class ship built.

USS New Ironsides Engine Room Clock, brass & glass, 1862, Naval Heritage and Command collection.

While Ericsson was busy building the USS Monitor in New York City, the well-known Philadelphia engine-building firm of Merrick & Sons made the proposal for a new wooden-hulled broadside ironclad, but they did not have a slipway so they subcontracted the ship to William Cramp & Sons Philadelphia shipyard. The ship was ordered by the Navy on October 15, 1861 and launched on May 10, 1862. William Cramp claimed credit for the detailed design of the ship’s hull, but the general design work was done by Merrick & Sons.

Named the USS New Ironsides in homage to the nickname of the frigate USS Constitution (”Old Ironsides”), the ship was a formidable vessel. It carried the firepower of eight monitors, had a four-inch solid piece of iron protecting its hull and included watertight compartments to protect against internal flooding.

Hardwired into the ship’s propulsion system, this clock could track the number of revolutions (the dial on the bottom) to help the chief engineer determine the ship’s speed. The clock’s internal workings have two white sapphires, a diamond and a ruby to reduce friction between moving parts. The clockface’s engraver mistakenly wrote Ironside instead of New Ironsides.

The New Ironsides spent most of her career blockading the Confederate ports of Charleston, SC, and Wilmington, NC, in 1863–65. Although she was struck many times by Confederate shells, gunfire never significantly damaged the ship or injured the crew. The ship was destroyed by fire in 1865 after she was placed in reserve.

John Adolphus Bernard Dahlgren, artist unknown, copy after Mariette Benedict Cotton (artist) and Mathew B. Brady (photographer), oil on canvas, ca. 1945, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

The son of Sweden’s Philadelphia consulate, John Dahlgren was among the US Navy’s most brilliant ordnance engineers. He introduced a new, lightweight howitzer in the 1840s and the “Dahlgren” smoothbore cannon in the mid-1850s. Unlike his competitors, Dahlgren’s guns were forged as one piece of iron. The result was a safer gun that never had any accidental breaches. The US Navy adopted this gun and used it on all its ships for the next 30 years.

Outside the museum on the east and west sides are two IX-inch (9 inch) Dahlgren smoothbore guns. This one on the west side is from the gunboat USS Osceola. It was cast in Boston by Cyrus Alger and Company in 1863 with a weight of 9,240 lbs. and was inspected by Timothy A. Hunt.

The gun on the east side is marked No. 1133. It was cast at the Fort Pitt Foundry in Pittsburgh with a weight of 9,225 lbs. and was inspected by John M. Berrien. The Navy placed this gun aboard the USS Ticonderoga in 1864 and it was used extensively during the bombardments of Fort Fischer in 1864 and 1865.

The carriages the guns sit on were constructed of iron after the Civil War to replace the original wooden carriages. The American Swedish Historical Museum acquired both cannon from the Naval History and Heritage Command in time for the Museum’s grand opening in 1938.

You must be logged in to post a comment.